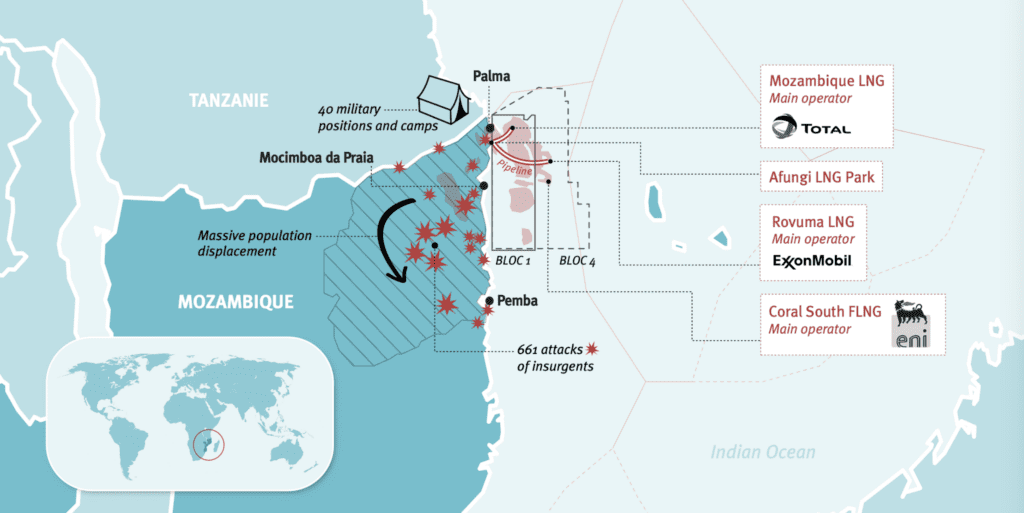

Violent attacks in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique’s most northern province, which forced major French corporation, Total Energies, to abandon1 its historic African mega-site, have mostly been labelled as Islamist jihadism. However, with just a little investigation, these supposed mujahideen are revealed to be more likely just another set of disenfranchised youths attempting to violently forge their own path.

The militant group attributed to these attacks is officially named Ahlu Sunnah wa-I-Jama’ah (ASWJ), but known locally as al-Shabab (no relation to the Somalia-based group). They are globally referred to as Islamic State in Mozambique (IS-Mozambique), thanks to a part of its personnel pledging allegiance to Islamic State (IS) in 20182.

However, the majority of fighters in this group are not idealistically aligned to IS and are instead more motivated by disenfranchisement.

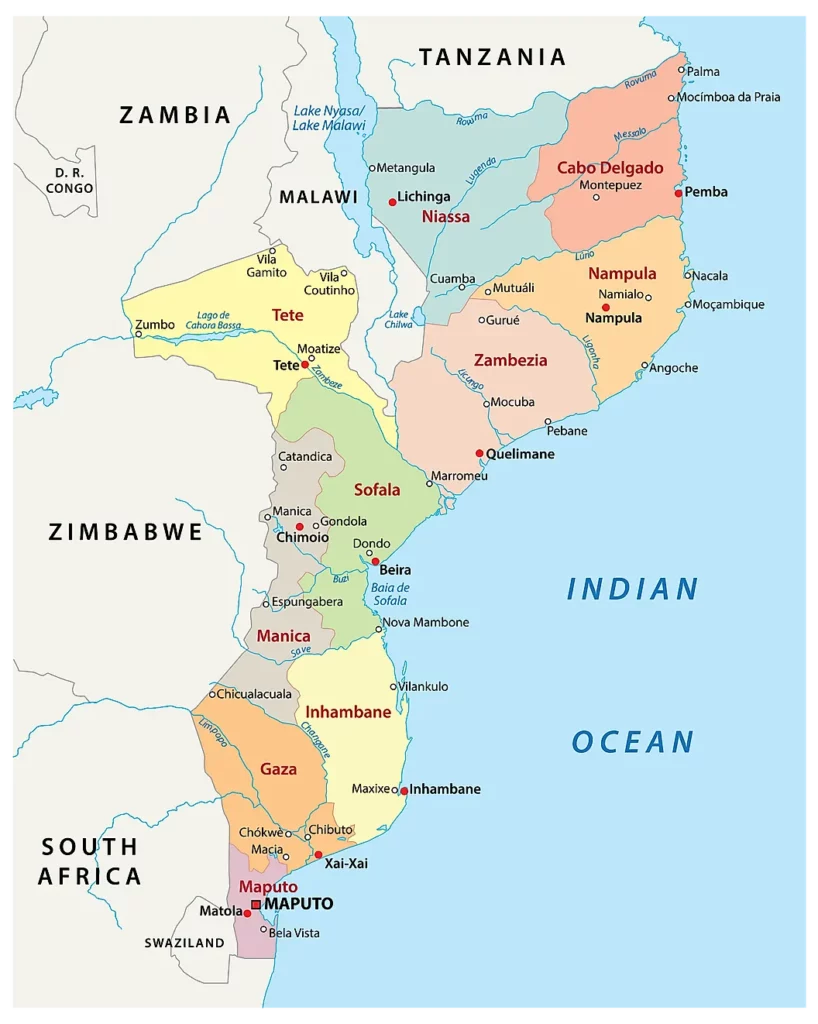

In similarity to many other African nations, Mozambique consists of numerous distinct ethnic groups with unique languages and cultures. Portuguese colonial rule bound these factions together for centuries, but once independence was gained, conflict erupted and resulted in a civil war. That war left the nation in a poor state, one that it has not yet recovered from.

The disenfranchisement at the heart of the troubles in Cabo Delgado can be sourced back to three key factors: Religious tension (owing to the local dominance of Islam over the nation’s and ruling elite’s leading religion of Christianity); inequitable development in the area compared to elsewhere (at least partially attributable to the capital Maputo being over 2000 Km away); and the lack of employment opportunities in the area (exacerbated by a surplus of youths3 and the extraction of wealth by non-locals).

The discovery in 2010 of Africa’s largest natural gas deposit off the coast of Cabo Delgado initiated a goldrush, one that should have benefited locals. In actuality, richer southern Mozambiquans and foreigners, including multinational corporations4, have exploited the situation to fill their own pockets, leaving the locals often worse off than before. A point reinforced by the claims of locals that they were literally told by a district administrator to not stand up and complain about gas extraction projects as that would harm the future of Mozambique5.

Many in the area label the attacks as a ‘rebellion incited by decades of neglect by a government that has never cared for the region, and argue that the supposed Islamists are in truth simply unemployed youths or frustrated farmers and fishermen.’6

This rational argument contrasts greatly to the notion that these militants fight solely for Islamist Jihad. It also adds significant weight to the narrative that IS’s influence has waned sufficiently to a point that it now falsely claims control and influence over the acts of disenfranchised youths in parts of the world that are so far removed from their spiritual heartland of Syria and Iraq, and of which they were once completely disinterested.

1 https://news.mongabay.com/2021/04/gas-fields-and-jihad-mozambiques-cabo-delgado-becomes-a-resource-rich-war-zone

2 https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/islamic-state-mozambique

3 Mozambique can be said to have a stage one growing population, with both high fertility and birth rates as well as high mortality rates and lower life expectancies. It also has a median age of only 17. Mozambique Population Pyramid 2024 – https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/mozambique

4 ExxonMobil (USA), in partnership with ENI (Italy) and CNPC (China) are also invested in projects in Cabo Delgado. https://allafrica.com/stories/202408150291.html

5 https://news.mongabay.com/2021/04/gas-fields-and-jihad-mozambiques-cabo-delgado-becomes-a-resource-rich-war-zone

6 https://www.nzz.ch/english/terrorist-attacks-delay-gas-extraction-project-in-mozambique-Id.1825631